China’s President Xi Jinping visited Myanmar and made a push to rev up big infrastructure projects under his Belt and Road initiative, seeking to cement Beijing’s role as the country’s closest international partner while Western governments hold back over human-rights violations.

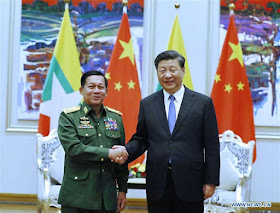

Mr. Xi’s two-day visit—the first by a Chinese head of state in almost two decades—comes as Myanmar is facing allegations at the International Court of Justice that its security forces committed genocide against the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority. Last month, Washington imposed sanctions against four military officials, including the commander-in-chief.

China has backed Myanmar through the crisis and is now stepping up efforts to secure the strategically located nation as a major partner in the region. Mr. Xi held talks with Myanmar’s main civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, in the country’s capital Naypyitaw on Saturday.

The two sides signed a raft of agreements to advance the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor—a multibillion-dollar package of infrastructure, trade and energy projects designed to link landlocked southwestern China to the Indian Ocean.

“We are drawing a future road map that will bring to life bilateral relations based on brotherly and sisterly closeness in order to overcome hardships together and provide assistance to each other,” Mr. Xi said in a speech Friday.

The planned corridor includes a deep-sea port and a special economic zone in Kyaukpyu on Myanmar’s western coast, and a railway line from China’s Yunnan province. The Kyaukpyu port has been significantly scaled down from what was originally envisioned as a more-than $7 billion development, but it remains a key investment. A new urban development close to Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon, is also in the cards.

The Southeast Asian nation has so far moved cautiously in embracing Chinese investments, which have long been viewed with skepticism in the country. Following local opposition over the displacement of residents and environmental impacts, Myanmar suspended a major China-backed dam project in 2011, which became a symbol of fraying ties between the two neighbors.

In remarks on Friday, Ms. Suu Kyi emphasized the need to prevent environmental degradation and consider development for the people in implementing new projects. Myanmar held democratic elections in 2015, ending decades of military rule that had led to diplomatic and economic isolation. Ms. Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, led her party to victory in those polls, though the military kept a grip on key levers of power.

The initial transition ushered in rapprochement with Western governments that lifted economic sanctions, paving the way for trade and investment. President Barack Obama visited the country twice during his presidency, and hosted Ms. Suu Kyi at the White House in 2016 shortly before sanctions were eased.

Then the military launched brutal operations in 2017 that forced more than 700,000 Rohingya to flee across the border into Bangladesh. Refugees shared stories of mass killings, rape and the destruction of villages by security forces. Amid a global outcry, the U.S. urged Myanmar to hold the perpetrators accountable and relations grew strained. Myanmar says it was conducting counterterrorism operations and its security forces didn’t systematically use excessive force.

“It was Beijing’s opportunity to save the day and restart its moribund economic corridor in exchange for diplomatic protection,” David Mathieson, an independent analyst based in Yangon, said. “In effect the West won, then lost, Myanmar, and the major factor is the Rohingya crisis.”

Policy uncertainty and complex due diligence requirements also make Myanmar a difficult place to do business, analysts and business representatives said. “Myanmar’s investment environment is not really attractive to Western investors,” said Khin Khin Kyaw Kyee, head of the China desk at the Institute for Strategy and Policy in Myanmar. “After the rapprochement began, people hoped investment would come in, but it just didn’t materialize.”

Beijing meanwhile took a “multilayered” approach to courting Myanmar, ramping up sponsored visits for business leaders, politicians and civil society representatives to improve perceptions of China’s political and economic model, Ms. Khin Kyee said. But Chinese megaprojects still face pushback, particularly when they cut across the country’s many conflict zones where the army is battling ethnic rebel groups seeking greater autonomy.

Taiwan's presidential election on January 11 made Chinese foreign policy look messier than it actually is. Tsai Ing-wen won a handsome victory on a wave of umbrage against China's habit of pushing its smaller neighbors around. Her landslide suggested missteps and overreach by President Xi Jinping too.

That impression appeals to China's critics, especially in the U.S., who like to view Xi as a bully. Sadly for them, it is far from an accurate reflection of Beijing's steady and largely successful recent increase in influence elsewhere in its neighborhood.

A better picture of China's progress will be on show when Xi arrives in Myanmar on January 17, the first visit by a Chinese leader in nearly two decades. More to the point, it will underline the impotence of nations like the U.S., Japan and India, as they try to balance and blunt China's rise.

Despite its tiny economic size, Myanmar remains a strategic prize for Beijing, in part because it hosts a clutch of infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi's signature foreign policy program. Xi's aim during his two-day visit will be to push forward the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, a multibillion dollar package of port, rail and power projects, as well as a new city close to commercial capital Yangon.

Many BRI projects are white elephants -- expensive and pointless. But its schemes in Myanmar have a reasonably sound commercial logic, linking China's landlocked western provinces to the Indian Ocean. They carry within them a much grander vision too: a long-cherished "two-ocean" strategy, in effect extending China's western reach to the Bay of Bengal.

At one level, China's interest in Myanmar should bring it benefits, not least tens of billions of dollars in badly-needed investment. But in truth, it leaves the country in a deep political fix. Some of this involves specific worries about China's largesse, and with it the risk of debt trap diplomacy.

BRI

projects are often excessively costly. Myanmar managed to renegotiate the cost

of its planned Chinese-built Kyaukpyu deep-sea port on the Bay of Bengal down

from around $9 billion to just $1 billion. Now it must do the same for a pricey

rail line between Yunnan province and Yangon, which some estimates suggest

might cost also $9 billion.

The larger problem is political, however. China remains remarkably unpopular in Myanmar, the legacy of its ties with the country's old military rulers. Xi has done little to help his case by continuing to push much-hated projects, notably the temporarily mothballed Myitsone mega-dam on the Irrawaddy river.

Many in Myanmar suspect, probably correctly, that China would like it to become a pliant vassal state. With an election later this year, Aung San Suu Kyi and her ruling National League for Democracy badly want to avoid being seen as Beijing's lackeys.

Suu Kyi's strategy has thus far been to prevaricate, delaying some of China's megaprojects until after the election at least. But Xi's arrival suggests this time-wasting approach may be running out of road. His mere appearance requires that new projects be announced, along with the usual flurry of pledges of undying friendship.

This leaves Myanmar facing an awkward dilemma about its dependence on its larger neighbor. Its civilian and military leadership have tried hard to avoid this fate, suggests Richard Horsey, a political analyst based in Yangon.

But allegations of genocide in Rakhine State, which Suu Kyi denied publicly at the International Court of Justice in The Hague during December, have left her country with few other friends. The government "finds itself in exactly the position it has desperately tried to avoid," Horsey says. "China has Myanmar over a barrel."

China would still be wise not to overplay its hand. Recognizing Myanmar's internal political constraints could avoid the kind of backlash that its pushiness caused in Taiwan. As China seeks its own west coast, a calmer approach is almost certainly the most likely route to success. Yet if Xi's arrival proves awkward for Myanmar, it is doubly so for the region's other powers, and especially those, like the U.S., Japan and India, which are alarmed at the speed of China's progress.

True, Japan has put plenty of money into infrastructure. The U.S. quietly helped officials in Naypyidaw renegotiate the Kyaukpyu port too. But neither nation comes close to matching China's plans. Despite its geographic proximity and historical ties, India's approach is mostly feeble and self-interested. None of the three, either separately or together, has an effective plan to help Myanmar keep a respectable distance from China's embrace.

This is true elsewhere around Asia too. China has made relatively few aggressive moves in its own backyard over the last couple of years. Instead, its leadership has been forced to focus on managing trade-war ties with a tempestuous U.S. president while also trying to deal with internal trouble spots in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

Even so, around Southeast Asia in particular, its policies are succeeding in -- gradually but inexorably -- increasing its influence. And Beijing will continue to push, seeking to extend its reach both in particular countries and broader areas like the South China Sea. The more it does so, the clearer it becomes that those nations which aspire to balance China's rise are failing in that task. Myanmar would be a good place to start.

Related posts at following links:

Myitsone Dam: China Demands Payback For Protection

General Min Aung Hlaing In China To Thank President Xi