(Jason Tower’s post from The U.S. PEACE INSTUTUTE on 5 December 2024.)

Myanmar’s Resistance Manages to Defy Chinese

Pressure — For Now: Since August,

China has tried to weaken Myanmar’s resistance forces while offering legitimacy

to the junta. Many elements of the resistance are defying Chinese demands, but

tension and instability are rising. Myanmar may become a test case for more

robust Chinese security involvement overseas.

In early August, resistance forces in northern

Myanmar delivered yet another historic defeat to the Myanmar military. After

just 35 days of fighting, resistance actors toppled the Myanmar army’s

northeastern command, bringing expansive amounts of territories across northern

Shan State under their control. These developments rippled through Myanmar and

reinvigorated the resistance — but also triggered a dramatic response from the

Chinese Communist government.

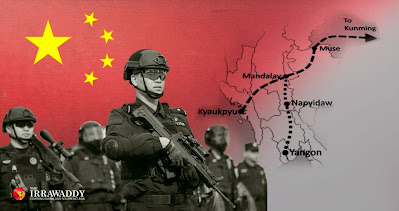

Since August, China has unleashed punitive measures targeting key resistance groups, greenlit military airstrikes across northern Myanmar to push ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) out of newly captured territories, and showered Myanmar junta leader Min Aung Hlaing with unprecedented levels of legitimacy.

Despite this, resistance forces have shown

significant resilience to Chinese pressure and defied Beijing by continuing

revolutionary activities in both the northern and southern parts of the

country. Additional victories in November have brought some of the world’s

richest rare earth deposits under the control of resistance forces, creating

challenges for China’s dominant position in this market.

Despite this, resistance forces have shown significant resilience to Chinese pressure.

China’s response to these developments has

implications far beyond Myanmar, as it could set precedent for more aggressive

Chinese actions in other geopolitically sensitive hotspots and with respect to

how it secures its investments overseas.

The resilience of resistance forces — and their

growing leverage over the Myanmar economy — also provide a unique opportunity

for other international actors. The United States, other Western countries and

India should adopt much more deliberate and effective strategies to prevent

China from gaining a strategic advantage in Myanmar.

A Historic Series of Resistance Victories

From mid-January until mid-June of 2024, a

Chinese-brokered cease-fire (referred to as the Haigeng Agreement) effectively

froze the conflict in northern Shan State, where the Myanmar National

Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA)

and the Arakan Army — collectively known as the Three Brotherhood Alliance, or

3BHA — had been fighting against the Myanmar military.

Beijing spent much of this period pushing the

involved parties to achieve a more elaborate deal so China could resume its

trade and economic cooperation in the region. But instead, both the Myanmar

military and the 3BHA spent this period preparing for the resumption of

hostilities. Consequently, talks collapsed in mid-May. A month later, on June

13, the Haigeng Agreement collapsed as well. In defiance of Chinese pressure,

the parties were back at war.

This shouldn’t have come as a surprise to China.

But what likely did catch Beijing off-guard was the rapid pace at which the

3BHA began rolling over one military post after another, capturing a series of

major townships in northern Shan State in just weeks.

By early July, fighting reached the largest town in

northern Shan State, Lashio, which was also home to the Myanmar military’s

northeastern command. After several weeks of fighting, the entire town of

Lashio — as well as the command — fell to resistance forces on August 3.

China Intervenes to Save a Military Regime on the Brink

For the first two weeks of August, resistance

forces continued to press onward, giving the impression that they would move

into Mandalay.

Rumors began to spread — even on Chinese-language

social media outlets — that a deal had been cut between the MNDAA and the

National Unity Government (NUG) to stand up an NUG office in Lashio and make

MNDAA leader Peng Deren the new vice president once the military is defeated.

While the MNDAA later dismissed these statements as

disinformation, by then, China had already set an unprecedented response in

motion.

Throughout the remainder of August, China proceeded

to cut off all resource flows to resistance forces in northern Shan State.

China also closed off border crossings, cut electricity and internet, and even

placed pressure on the most powerful northern EAO — the United Wa State Army

(UWSA) — to adopt the same policies in its own dealings with the MNDAA and

TNLA.

The extent that China was bullying the EAOs became apparent when leaked details of an August 27 meeting between a Chinese diplomat and two senior UWSA leaders began circulating.

The leak revealed that China believed the MNDAA’s

capture of Lashio had “deeply damaged China-Myanmar friendship,” and that the

resumption of Operation 1027 had undermined Chinese interests. China also

blamed the UWSA for failing to completely cut the flow of power, water,

internet, basic supplies, and people into MNDAA territory.

China’s bottom line: This “5-cuts policy” should

continue to be enforced on the TNLA and MNDAA until they end involvement in

revolutionary activity and the latter hands Lashio back to the Myanmar army.

In September, Chinese pressure on the EAOs

increased even further. China traditionally responds strongly to airstrikes

conducted along its border. But when Myanmar’s military regime indiscriminately

perpetrated airstrikes on MNDAA and TNLA positions across Shan State, Beijing

stood and watched — even refusing to respond when airstrikes hit one of the

most important Chinese temples in Lashio.

In early November, in response to Chinese pressure

to cut off flows of goods into MNDAA territory, the UWSA publicly convicted 9

people for smuggling goods into “conflict areas” in northern Shan State.

However, the most concerning development of all was

the sudden disappearance of MNDAA leader Peng Deren. Peng was last seen

publicly in mid-August. According to EAO sources, Peng traveled to the Chinese

city of Kunming for health reasons in mid-September but has been out of

communication since.

Officially, China maintains that Peng is in Kunming for medical treatment. But Peng’s lack of communication is very unusual given his high profile. It is also notable that the leaked meeting minutes referenced above showed Chinese officials questioning how much longer Peng might remain the leader of the MNDAA.

In addition to all this, China invited Myanmar

junta leader Min Aung Hlaing to visit in early November. Beijing had snubbed

the general in recent years, refusing his participation at signature Belt and

Road Initiative events.

While Min Aung Hlaing was not afforded a trip to

Beijing or a meeting with Xi Jinping, the visit was a windfall: The junta

helmsman was able to engage with leaders from a range of subgroupings within

ASEAN. This flurry of meetings sent a strong signal to ASEAN that both China

and subregional blocs preferred re-engagement with the Myanmar military at the

highest levels.

The Price of Chinese Assistance

Immediately following Min Aung Hlaing’s return from

China, the quid-pro-quo became clear. In exchange for this support, China

demanded a major concession from the Myanmar army: Changes to the country’s

laws to establish a joint venture security company that would permit China to

directly secure its cross-border investments in Myanmar, including through the

deployment of armed Chinese security guards.

The Myanmar military opted to divulge information

about China’s request to the public — an indication that the Myanmar military

sees this move as controversial. The move breaks the Myanmar military’s

monopoly on providing security services for Chinese projects in the country,

which is one of the most significant sources of leverage that it holds against

China.

Min Aung Hlaing might be able to argue this could

provide the Myanmar army with new access to equipment and intelligence — and

that the presence of highly trained Chinese security could also free up Myanmar

military troops, security guards and police to be redeployed to the front lines

against resistance forces. But there is also the distinct possibility that once

in the country, Chinese security could act in ways counter to the military’s

interest.

Belt and Road in the Crossfire?

China’s desire to directly secure its investments

in Myanmar is based on highly problematic logic. Coupled with China’s openly

hostile posture toward resistance forces, this desire could draw Chinese

investments directly into the crossfire.

By partnering with the Myanmar regime to gain

access for Chinese security personnel, China is ignoring the fact that vast

territories — including many of the areas through which Chinese projects run —

are no longer under the control of the military. As such, the population and

vast ranks of resistance forces are now likely to see these projects as aligned

with an enemy force.

Chinese analysts have proposed a scheme to address

this issue: Have the security company recruit from the ranks of the EAOs and

Peoples Defense Forces. However, this is only likely to trigger much greater

chaos in Myanmar.

Resistance actors could struggle to identify

strategies to prevent movements for federalism, democracy and the end of

military dictatorship from being overrun by Chinese economic interests. The

military might also move to prevent resistance actors from infiltrating the

security company, dragging these projects even further into the conflict.

China’s Plans for Myanmar’s Future

The contours of China’s game plan for Myanmar are

increasingly clear: First, through a combination of bullying, economic coercion

and the manipulation of tensions across Myanmar’s EAOs, China aims to fragment

and ultimately undermine resistance forces while supporting the Myanmar

military. The end goal is to secure a series of deals that place the country on

a trajectory toward consolidation of military rule and cease-fire capitalism.

Second, seeing the junta’s decreasing capacity,

China aims to directly secure its geostrategic investments and assets in the

country. They may use their ongoing influence over northern EAOs as leverage to

compel the Myanmar military to trade away some measure of sovereignty to enable

this.

Third, by using leverage and divide-and-conquer

tactics through mini-laterals and subregional platforms, China aims to tilt

ASEAN and other external actors in the direction of normalizing ties with the

military regime.

And fourth, through support for a junta-led

election, China aims to help the regime achieve its so-called five-point

roadmap toward “stability.” China has

followed a small number of other international actors in arguing that a

junta-led election might open space for reform in the country.

While it is extremely unlikely that Min Aung Hlaing

has made any such commitments, this argument is predicated on the assumption

that the general will relinquish his control over the Myanmar military

following such an election — a step that Min Aung Hlaing is almost certain not

to take.

However, even if Min Aung Hlaing were to make such

a commitment, there is no case to be made that any election conducted under

current circumstances would be anything other than a catalyst for greater

violence.

EAO Resilience

The change in China’s posture has significantly

impacted the resistance. But surprisingly, resistance actors are defying

Chinese pressure across the country on an ongoing basis.

The front lines of this defiance are in Kachin

State, where the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) has significantly picked up the

pace of its military operations since mid-August. Despite Chinese demands that

it cease fighting and negotiate with the regime, the KIA recently defeated a

Myanmar military-aligned militia with close ties to China.

Known also as the “rare earth militia,” the group

has aligned closely with Chinese mining companies since 2016 to transform

Kachin’s Pang War township into the primary source for rare earth imports into

China.

But in late October, the KIA took control of the

whole of Pang War, bringing all of the mining operations under its control.

This prompted Chinese industry insiders to publicly announce a coming surge in

prices — sparking significant volatility in the Chinese stock market in

November.

Signaling just how big of a shock this was to

China, the Chinese government undertook a massive overhaul of the leadership of

six of its top mining companies just days later, and banned rare earth exports

to the United States.

With billions of dollars in rare earth mines now

under its control, the KIA sent an even bolder signal to China: It announced

the closure of the key border crossing servicing the rare earth mineral

industry, indicating that they are in no hurry to resume business as usual.

The KIA’s moves are likely driven not only by a

desire to avoid being bullied by China, but equally by the Kachin public, which

has repeatedly protested the serious environmental and health impacts of the

rare earth mining. If the KIA does not introduce more sustainable practices, it

will likely come under popular pressure.

The KIA is not alone in its resilience. Despite the

pressure from China, the MNDAA has continued to hold its ground in Lashio

despite issuing a series of statements that it will not engage in any further

movements toward Mandalay. Meanwhile, in Rakhine State, the Arakan Army presses

ahead with military operations and has not indicated any concerns related to

Chinese pressure.

International Implications

While China continues to pay lip service to ASEAN

centrality and leadership on the Myanmar issue, it has emerged as the dominant

external actor pushing to shape developments to its advantage.

In many respects, Myanmar is emerging as a test

case for more robust Chinese security involvement overseas. Everything is on

the table, from deploying Chinese police, to using technology to monitor and

surveil activities beyond China’s border, to rolling out new approaches for

overseas security on Belt and Road Initiative projects, to gaining a strategic

advantage in platforms such as ASEAN.

In many respects, Myanmar is emerging as a test

case for more robust Chinese security involvement overseas.

Despite this interference — and the tensions and

chaos that it has triggered — Myanmar’s resistance forces are remaining

resilient and have gained very significant economic leverage over both China

and the military regime. More importantly, they are now ultimately the only

players in Myanmar that can provide a viable path for a return to stability.

The United States, other Western countries and

especially India should take careful note of the critical role that Myanmar’s

resistance can play and consider how they might leverage the incredible

resilience and growing influence of these resistance forces vis-à-vis China’s

moves to exploit Myanmar to its strategic advantage.

They should also look closely at the shifting

control over critical rare earth minerals in northern Myanmar, and the possible

implications for breaking down China’s dominance of rare earth mineral supply

chains.