(Staff post from the ECONOMIST MAGAZINE on 30 May 2025.)

IN LATE FEBRUARY a plane carrying 25 Chinese

mercenaries landed on Ramree Island, off the coast of Myanmar. Their arrival,

at an airfield in the midst of a chaotic battle, is a sign of China’s growing

influence throughout the country.

Since a coup d’état four years ago brought a

military junta to power in Myanmar, China has become the most important actor

in its southern neighbour’s affairs. Western countries have mostly looked away

as Myanmar’s struggle for democracy has turned chaotic and violent.

China has filled the resulting vacuum, working with both the junta and a vast array of armed rebel groups to advance its own agenda. China’s interests in Myanmar are varied. They include stability along the 2,100km (1,300-mile) border and the suppression of Western influence.

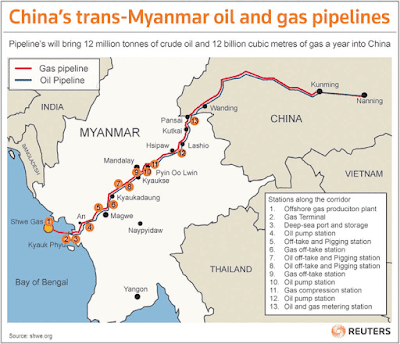

They also include the protection of an oil-and-gas

pipeline that snakes for 2,500km from Ramree Island north-east across Myanmar,

through the area devastated by an earthquake in late March, to Kunming, capital

of Yunnan province in south-western China. Perhaps the best way to understand

how China has prosecuted its interests is to follow this pipeline.

The pipeline carries only a fraction of China’s

imports of oil and gas—enough for the south-west but not the whole country. But

it allows supplies to bypass chokepoints in the Strait of Malacca and the

Indonesian archipelago. If China and America ever went to war, it would become

a critical economic lifeline.

The pipeline is also a cross-section of Myanmar’s

civil war: no part of its route has been untouched by conflict. Yet it remains

almost entirely unmolested—testimony both to China’s adroit diplomacy in

violent, fast-changing circumstances and to its cold, self-interested approach

to the charnel house across its border.

Rakhine state (Arakan State)

The Chinese mercenaries on Ramree Island, probably

ex-soldiers, are not there to help the junta fight the Arakan Army (AA), an

insurgent group that now controls much of Rakhine state, dominated by ethnic

Rakhine. China’s goal is instead to protect investments in its outlet to the

Indian Ocean. As well as the pipeline terminals, a deep-sea port is planned

nearby. A proposed railway would connect it to China.

In fact, both the junta and the AA approved the

mercenaries’ deployment. The junta passed a law legalising the presence of

foreign mercenaries, putting aside its deep historical hostility to foreign

soldiers in Myanmar. The AA’s sign-off was less formal. “Of course, they kind

of have to” agree to it, according to someone with knowledge of its

deliberations.

In Myanmar today, no armed group dares alienate

China. Rakhine state achieved international notoriety in 2017 after Myanmar’s

army, the Tatmadaw, carried out atrocities against the Rohingya, a Muslim

minority. At least 6,700 people died. Another 700,000 Rohingya were pushed into Bangladesh, where most remain in what

has become the world’s largest refugee camp.

The next year the AA led the Rakhine, the largely

Buddhist local majority, in an uprising against the Tatmadaw. Fearing this to

be the first step in the disintegration of Myanmar, the army and the then

civilian government, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, sought to crush it. A ceasefire

was negotiated in November 2020. After the coup three months later, other

ethnic armies across Myanmar rose against the junta, in collaboration with

pro-democracy forces. But the AA bided its time.

In late 2023, as the Tatmadaw came under pressure elsewhere, the AA (with 150,000 men) broke the ceasefire. The junta, short of men, then did the unthinkable: it began arming Rohingya to fight for it against the AA. This did it little good: within a year the Tatmadaw had lost most of Rakhine state. Not since the years immediately after independence in 1948 has the military suffered such a string of defeats anywhere in Myanmar.

You might suppose this would concern China,

considering its strong relationship with the Tatmadaw and its investments in

the state. But no. China has long also cultivated the AA. It has been relaxed

about the AA’s rapid progress, and the AA has reassured China that it supports

the investments. It has taken care to avoid using heavy weapons near the

pipeline; and as it has captured a series of pumping stations, it has allowed

oil and gas to flow unimpeded.

The Dry Zone (Middle Burma)

From Rakhine state, the pipeline crosses the Arakan

mountains to wind across the Dry Zone, a region of arid plains that is the

heartland of Myanmar’s Bamar majority. For decades the Tatmadaw has recruited

heavily among young Bamar there. Even as the periphery of the country suffered

wave after wave of conflict after independence, the Dry Zone remained mostly

peaceful for 50 years.

But something changed after the coup in 2021. When

the junta met peaceful protests against its rule with gunfire, young people in

the Dry Zone took up arms. They formed resistance units and began to ambush

army convoys. In time, some of these units began to work together. Most

remained independent, but others declared their loyalty to the National Unity

Government (NUG), elected lawmakers opposed to military rule living abroad or

under the protection of ethnic armies.

At first, those who joined the resistance were nearly as hostile to China as to the junta. Many assumed that China had green-lit the coup, recalling its support for a previous military government, in power from 1988 to 2011. So the pipeline was high on their list of targets. But the NUG ordered them to stand down, fearing that an attack on the pipeline would upend its bid to be seen by China and the world as Myanmar’s legitimate government.

Nevertheless, the pipeline has come under fire.

Around Natogyi, 50km from Mandalay, Myanmar’s second city, guerrillas attacked

the pipeline in February 2022 and (twice) in May 2023. But the poorly armed

groups did little damage. In subsequent days the army rounded up dozens of

their civilian supporters, seeking to show China that it would stoutly protect

its investments.

These days, one resistance commander tells The Economist, they don’t need to be told not to attack the pipeline. It works against their interests, he says. China controls their supply of arms and ammunition—and occasionally heavier munitions—through proxies on the border. When the resistance angers China, supplies stop, sometimes for months.

The resistance has struggled to take and hold

villages or towns. In August 2024 it seized Natogyi for just a day, retreating

when Tatmadaw reinforcements arrived. But in the countryside, where these

groups are strongest, supportive civilians carry out government functions, such

as schooling.

The Dry Zone was among the areas hit hardest by the

earthquake that struck Myanmar on March 28th; the epicentre was near Sagaing

city, 20km from Mandalay. The quake, which had a magnitude of 7.7, is known to

have killed more than 3,000 people and injured a further 4,600.

But aid workers have struggled to reach areas where

resistance groups hold sway, and news has been slow to emerge from areas long

subjected to internet blackouts by the junta. It is not yet clear whether the

pipeline has been damaged. If it has been, Chinese engineers, unhindered by

either side, are likely to get to the area faster than relief efforts.

Shan State

Near Mandalay, the pipeline climbs out of the Dry

Zone up a steep escarpment marking the start of the Shan Hills, named after the

local ethnic-majority group. Ethnic armies have long occupied some of the

hills, and early on after the coup, the junta worried about the pipeline being

attacked. It planted landmines along the approaches to it.

Much of the pipeline’s route in Shan state was then

under the junta’s control. Now, shortly after it passes the picturesque hill

station of Pyin Oo Lwin, home to the Tatmadaw’s military academies, it is in

rebel territory up to the Chinese border at Namhkam. The junta has China,

scammers and itself to blame for this reversal of fortune.

From compounds along the border, scammers ran

fraudulent schemes to bilk Chinese savers, often employing Chinese people

trafficked to work against their will. In 2023 eliminating these centres became

a new objective for China in Myanmar. But Myanmar’s Border Guard Forces—old

ethnic militias which had made a deal to share authority and revenue with the

Tatmadaw—taxed the scammers and allowed them to flourish. Despite repeated

entreaties from China in 2023, the junta would not, or could not, shut the compounds

down.

Analysts say that China, fed up, authorised the

Three Brotherhood Alliance, a loose coalition of the AA and two older armed

groups, MNDAA the Kokang Army and TNLA the Palaung Army, to seize the border

town of Laukkaing and clean out scam compounds.

On October 27th 2023, the Brotherhood attacked Tatmadaw positions across hundreds of square kilometres of Shan state. It was a rout. Thousands of Tatmadaw soldiers surrendered. Operation 1027 (named after the date) made the Brotherhood groups the most important rebel forces in Myanmar.

After the rebels took Laukkiang, China quickly

pushed the groups to accept a ceasefire. But it could not put the cork back in

the bottle. In June 2024 the Brotherhood broke the truce. Within weeks one of

the groups, MNDAA the Kokang Army, took Lashio, a city of 100,000 in eastern

Shan state and the biggest to fall to an ethnic armed group in Myanmar’s

history. The third member of the Brotherhood, TNLA the Palaung Army, started

down the road to Mandalay.

By August it had nearly reached Pyin Oo Lwin. China

was displeased by these developments. Though willing to work with any armed

group in Myanmar, it had become concerned that the junta might collapse under

the Brotherhood’s advance, setting off a conflagration that it could not

extinguish.

To regain control of the situation, it cut off trade with the Brotherhood, including in electricity and water. It also kidnapped the leader of (MNDAA) one of the groups. On April 22nd the Brotherhood withdrew from Lashio. In a scene which shocked Myanmar nationalists, Chinese diplomats supervised the return of the junta to the city. But fighting along the new front line continues.

(Cut Five Cuts: China Blockading MNDAA the Kokang Army)

All of this has exposed the pipeline to fierce

fighting, particularly in Hsipaw and Nawnghkio townships. Some locals there

fear that Tatmadaw pilots, no great marksmen, might bomb it by accident. But

over time, they have come to understand that no party to the civil war can

afford to anger China. Now civilians shelter near it, knowing that it is the

last thing either side wants to hit.

China (Big Brother)

China has always taken a keen interest in what

happens in Myanmar. After the Communists won China’s civil war in 1949, tens of

thousands of defeated Nationalists, or Kuomintang, took refuge in the Shan

Hills, launching incursions into Communist Yunnan across the border for years.

The Kuomintang are now long gone, but to forestall

any future threat, China works with anyone in Myanmar with guns. It is most

comfortable with the junta and those ethnic armies that eschew ideology for

aggressive nationalism. But it has also worked, if indirectly, with

pro-democracy resistance groups to protect its interests, such as the pipeline.

This approach has made China the most powerful player in the grim drama of

Myanmar’s civil war.

In the days after the coup in 2021, Myanmar’s

revolutionaries were prepared to sacrifice good relations with China for

Western assistance. It would have represented a dramatic shift in the country’s

geopolitical orientation. But as the war ground on, the promise of Western

assistance went unfulfilled, and these groups began to look towards China, too.

In January 2024 the NUG released a ten-point policy

on relations with China, in which it promised to respect China’s interests in

Myanmar, including investments like the pipeline. More important than the

details of the NUG’s commitments was its use of a word that China was looking

for: pauk-phaw, a special term in Burmese for relations between the two

countries. It is one of kinship between an older and younger brother. Whoever

rules Myanmar, its big brother will be watching.