(Allegra Mendelson’s article from the WASHINGTON POST on April 9, 2021.)

YANGON, Myanmar

— "Why don't you come see for yourself?" asked the foreign lobbyist

who had recently been hired by Myanmar's new military junta. Ari Ben-Menashe

and I had been speaking for a separate article I was writing on Southeast Asian

nations’ involvement in Myanmar.

Working for the military regime that ousted the

elected government in February, he belittled the size of anti-coup protests and

said he wanted me to see the situation firsthand. I was skeptical but intrigued

by the proposal — and it was the only way a foreign reporter could get into

Myanmar.

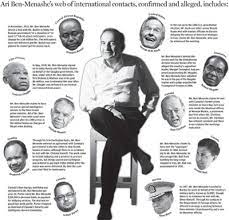

Ben-Menashe, a Canadian-Israeli public relations

operative, is known for representing regimes no one else will touch, including

those of onetime Zimbabwe strongman Robert Mugabe and Sudan’s new military

leaders.

A few days later, after I sent over a copy of my passport, he called to say my request had been submitted to the “highest of levels” of Myanmar’s military regime. By March 25, I had a single-entry business visa, and would become one of four Western journalists to participate in the junta’s first attempt at international outreach since the coup.

The week-long

trip, which I made alongside a crew from CNN, became a clumsy attempt by the

regime to remake its global image. As in its effort to whitewash a scorched-earth

campaign against Rohingya Muslims, the Myanmar military is turning to

propaganda, as the world condemns it for a crackdown on protesters in which

more than 600 people have been killed.

I landed in

Yangon on March 30 on a relief flight from South Korea. I had been expecting a

handful of aid workers on the plane. Instead it was nearly full, occupied by

people from Myanmar — some repatriating to reunite with family, others to stand

in solidarity with the protest movement.

Even before I

entered Myanmar, it was clear that this wasn’t a normal assignment.

Ben-Menashe, or his assistant, would call me regularly in the lead-up to the

trip to reprimand me for asking questions about the itinerary or safety

protocols. “Why don’t you listen when I speak?” Ben-Menashe growled at me

during one particularly angry call. “Are you a child? Do you need permission

from your parents?”

Then, from the

moment we landed in Yangon, we were barred from moving around freely. I

corresponded digitally with high caution, using only a burner phone connected

to a VPN, concerned that all communications were closely monitored. It didn’t

matter in the end: After our first day in Yangon, WiFi across the city was

turned off, probably to limit what we could share online.

We were escorted

around Yangon by soldiers — first in uniform, then later in civilian clothing.

For the duration of our trip, these escorts monitored our every move, with

cameras and phones raised to record us. They even tried following us into bathrooms

at times. Our military liaison told me this was for “our own safety,” to

protect us against the “violators,” the term used by the military to refer to

the protesters.

It was also clear that the military wanted to claim transparency by showcasing the presence of international media. When we tried to photograph our military handlers, however, they would turn their heads. Attachment to this trip was not something that Defense Ministry staffers seemed to want recorded. After a photo of one of our minders was posted on Facebook, he was pulled from our convoy.

The caravan of

soldiers immediately aroused suspicion among those we drove past. I managed to

remain anonymous, but news of CNN’s presence quickly made international

headlines. On our first two days, we were taken to locations carefully selected

to showcase instances of violence on the part of protesters.

Myanmar’s

demonstrators have been overwhelmingly peaceful, but some have turned to

more-radical action they believe is necessary to counter bloodshed by the

military. We visited three township administration offices in northern Yangon,

as well as several of the factories that had been reportedly burned down by

protesters. This included the Gadamar Superstore in Mayangone township in

Yangon, still smoking when we arrived.

At each stop, we

were met by individuals with seemingly rehearsed tales of being attacked or

defamed by protesters. The stories were often hard to believe, with changing

timelines and little evidence. In several instances, the language employed,

especially the use of the phrase “human rights violations,” seemed crafted to

appeal to our sensibilities as foreign reporters.

On our last day

in Yangon, we were taken to 10-Mile Market in Insein township and were finally

exposed to a scene that more closely resembled the truth. Shortly after we

arrived, a rumble of noise began. Within seconds, the previously quiet street

was filled with the sound of people banging on pots and pans, an act of

anti-military disobedience that had become common across Myanmar since the

coup. I looked around as the noise grew and saw that nearly everyone in sight

was holding up the three-finger salute that has become a symbol of the protest

movement.

A man stopped in

front of me and explained what they were doing. “We beat the drums against the military

coup — this is our symbol. All Myanmar people don’t like the military coup;

they want an elected government — the government of Aung San Suu Kyi,” said the

60-year-old retired seaman, referring to the ousted civilian leader.

A young woman

approached as we were leaving and began to cry as she told me about what was

unfolding in her country. She knew the risk in speaking with me, but said it

was more important for her to share her truth. Both she and the man spoke on

the condition of anonymity because of safety concerns. “Please help us, we

really need it,” the young woman said. “They are covering up the truth. The

military wants to show fake news to the world.”

|

| Burmese photo of Clarissa Ward & CW's photo of Burmese. |

Soon after we left the market, we learned that two people who had spoken to the CNN crew had been arrested. This number would increase to 11 as the trip went on; most were eventually released. According to Ben-Menashe, even the military was upset by the arrests, because they overshadowed the rest of the tour. “They shouldn’t have been arrested in the first place,” Ben-Menashe said. “It was a local idiot cop that did it, and when the higher-ups learned about it, they were immediately released.”

After Yangon, we

drove to Naypyidaw, Myanmar’s ghost-town capital that, even pre-coup, had a

dystopian air. Fog rolled in as we drove down a 12-lane highway. It was still

the dry season in Myanmar, yet a storm had descended on the capital and it was

raining heavily.

Our time in

Naypyidaw had been planned around an interview with the military’s spokesman, Maj.

Gen. Zaw Min Tun, who maintained the false justification for deadly violence

against protesters that had been repeated to us throughout the tour. We

repeatedly asked our liaison and Ben-Menashe to speak with other members of

the military, especially those at the highest levels; each request was denied

or went unanswered.

“The protesters,

in violent manners, have blocked the streets and thrown stones at the police,”

said Zaw Min Tun. “At this time, we had to take necessary action against these

violent protesters.”

By the end of

the trip, the news of those detained for speaking to CNN dominated the

narrative, rather than the military’s version of events. For me, what remains

most poignant is the voices of people who spoke out against the regime — in

person, from balconies, in cars and online. “Please report back our real

stories,” one woman cried out to us.

Myanmar junta hires Israeli-Canadian lobbyist for $2M to defend coup

Ari Ben-Menashe

and his firm Dickens & Madson Canada will represent Myanmar's military

rulers in the US and try to convince Washington that Myanmar's generals wanted

to move closer to the West and away from China.

An Israeli-Canadian lobbyist hired by Myanmar's

junta will be paid $2 million to "assist in explaining the real

situation" of the army's coup to the United States and other countries,

documents filed with the US government have shown.

Ari Ben-Menashe

and his firm, Dickens & Madson Canada, will represent Myanmar's military

government in Washington, and lobby Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates,

Israel and Russia, as well as international bodies like the United Nations,

according to a consultancy agreement.

The

Montreal-based firm will "assist the devising and execution of policies

for the beneficial development of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, and

also to assist in explaining the real situation in the Country," read the

agreement, submitted on Monday to the Justice Department as part of compliance

with the US Foreign Agents Registration Act.

More than 60

protesters have been killed and 1,900 people arrested since February 1, when

Myanmar's generals seized power and detained civilian leaders including State

Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi.